One GPU, One Vote

Today you were passed over for a job. You were declined a loan. You, or perhaps your kid, were rejected from a top university. And you never even knew it happened. Every day, in some of the deepest, most constitutionally-protected parts of our lives, algorithms are making decisions in milliseconds that no face-to-face human could ever justify. We don't need an AI manifesto—we need a constitution. Under pressure, companies are debating ethical frameworks or empaneling advisory councils for AI. As it is being used today, AI is simply incompatible with civil rights.

How do I know? I was Chief Scientist at Gild, one of the first companies to use AI in hiring, and I built the system that passed you over for that job. When I took the role at Gild, our goal was to “take bias out of the hiring process” and discover job candidates that would otherwise be ignored. Our AI-driven product for large companies used machine learning to analyze hundreds of thousands of data points pulled from dozens and dozens of public websites, from LinkedIn to personal blogs. We could identify job candidates without relying on traditional resume signals (hint, hint: male, Ivy League, whitish. If Silicon Valley was Hollywood we’d have “MERITOCRACY” written in three-story white letters atop the San Mateo hills…and white would be the correct color). The AI that Gild invented had genuine promise to help recruiters break the habit of safe bets in hiring. And yet, it failed.

Whatever your personal aesthetics, I very much doubt that freaky tentacle porn makes for better programmers.

Back in 2011, the use of deep learning–the technology that has powered much of the rise of AI in the world today–was still in its infancy in the business world. We were exploring new ideas at Gild, and I believe that our approach broke ground that few have surpassed since. We still failed. Our system frequently found patterns and made recommendations that were a complete mystery to us. Our AI “loved” programmers who frequented one particular Japanese Manga site, strongly uprating their capabilities. (Whatever your personal aesthetics, I very much doubt that freaky tentacle porn makes for better programmers.) So, if you weren’t a manga fan, our system might have passed you over in favor of someone who knows the theme song to Starblazers... and you would never even know that it had happened.

AI Decides

When AI decides who gets hired you’ll never know why it wasn’t you. There is some definite gender and age imbalance in the Manga fandom in the US, but even I cannot say for certain what was happening in Gild’s algorithms. We weren’t alone. Amazon’s recent experiment training a deep learning AI to predict who they would hire produced an irreparably sexist system that downgraded resumes simply for including the word “women’s”. After trying for a year to fix their system by manipulating their training data, the engineers finally flushed the entire project.

Just as humans inherit biases and prejudices from their environment, an AI will inevitably do the same. Amazon wanted to build a better hiring system but refused to recognize the cognitive biases of its creators. These hiring technologies have tremendous potential to make us more efficient and competent decision-makers; however, a lack of transparency combined with the self-interest of the employer undermines accountability, leaving potential candidates like you without anyone truly acting on your behalf. A human being asking you about race or gender during the hiring process would be an actionable violation of your civil rights. AI doing the same without your knowledge is just as wrong but completely hidden from view.

Some companies have even begun toying with systems to automatically fire low productivity workers. But why fire people if you can “help” them choose to leave? At least one company is actively exploring a system that identifies employees who might become unhappy at work. The plan is to then target those employees with internal messaging encouraging them to leave happily and willingly. Others are developing machine-learning-based personality assessments that screen out applicants predicted to agitate for increased wages, support unionization, or demonstrate job hopping tendencies. It’s not clear that such systems could truly work, but predictive HR serving only the employer would tip an already unbalanced relationship wildly in the bosses’ favor.

AI is also deciding the prices you’ll pay. Long before deep neural networks came into vogue, algorithms for real time auctions and ad targeting gave birth to the massive online advertising industry. (What AI Winter? The one that gave rise to search, social networks, ad targeting, automated mapping, and other trillion dollar industries?) Every time you visit virtually any website in the world, a real-time auction takes place for your attention based on a model of your customer lifetime value derived from intrusive targeting systems. Advertisers then algorithmically bid against each other for space on that site. The advertisers, the ad sellers, and the site owners themselves all participate in this transaction1.

Ironically, the one person not involved in this auction for your attention is you.

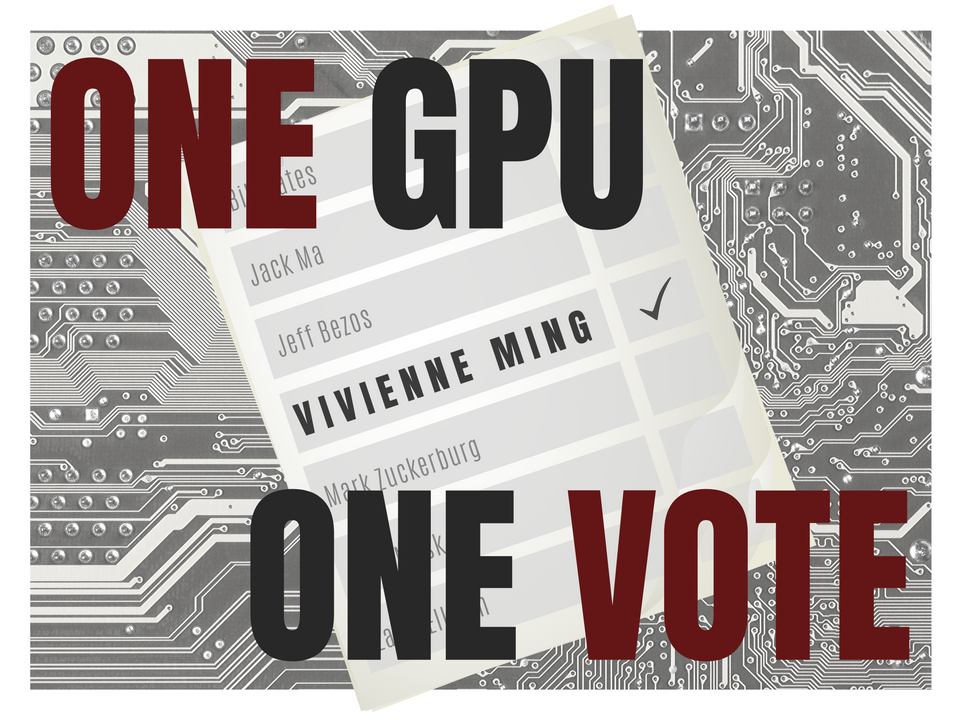

The problem is not the technology; it is the control of AI by a plutocratic few that threatens your civil rights.

You have no proxy in this auction for your attention beyond the goodwill of Google, Facebook, or Alibaba. You needn’t assume that Larry, Mark, Jack, or any of their billionaire brethren are villains to understand that their self-interest and that of their companies is not necessarily your own. The problem is not the technology; it is the control of AI by a plutocratic few that threatens your civil rights.

Many of these same tech giants would like you to believe that “solutions” like ethics councils will solve this problem. But Google’s AI Council and the World Economic Forum’s AI Ethics Council will not help. They assume that engineers are just not smart or wise enough to make ethical decisions. They assume ethics is an intellectual exercise when in fact it is an emotional one. When self-interest and social good diverge, these boards and councils become covers for the true AI decision-makers. (Of course, the one thing I love about most of these councils–Google, MIT, Stanford–is the deep insight that “What this problem really needs is a good white man.”)

Those ads aren’t just for diapers and reality TV. These algorithms decide whether (or not) to show high-paying jobs to women or to promote conspiracy theories and child porn. None of these are explicit decisions made by these companies; they result from greedy algorithms that optimize financial returns above everything else. If the most sophisticated companies in the world—Google, Amazon, Microsoft— have had very public missteps with AI, how can a consumer’s own interests ever compete? In fact, it’s very likely that businesses' AIs collude with each other in violation of antitrust laws, even without being given the go-ahead by their developers. Researchers at the University of Bologna have found that “Pricing algorithms can learn to collude with each other to raise prices”. Just wait until some opaquely complex AI playing the stock market decides it can earn more by shorting the market and crashing the system. Pitting self-regulation or even static laws on data ownership against such complex and dynamically evolving technologies will never keep pace with these threats.

Just as in hiring, algorithmic redlining emerges as AIs learn from, and even exaggerate, our own history of discrimination.

Beyond jobs, AI is also increasingly deciding who gets a loan and who doesn’t. Basic access to finance has been one of the most historically powerful tools for discrimination in America. Without access to capital, your dreams of owning a home or founding a business remain only dreams, redlined out of existence. Just as in hiring, algorithmic redlining emerges as AIs learn from, and even exaggerate, our own history of discrimination. This targeting of home loans and credit cards will not only leave out deserving “applicants” but will also supercharge predatory lending.

To combat these problems, many groups have called for ethics training for AI engineers, as though some of the smartest people in the world are simply uninformed of the implications of their work. The wild success of ethics training in business schools as well as my recent sexual assault by an Ivy League Religion scholar leave me in subtle disagreement.

The booming FinTech industry has positioned AI as both a tool for efficiency and for combating racial bias. These are desirable goals, but in none of these cases do algorithms actually act as blind arbiters for loans or insurance approval. Even if an AI works exactly as intended, avoiding all of the pitfalls these tangled webs of correlation produce, they are still solely designed to optimize the financial returns to the industry. The loan application process is already impenetrable to most, and now your hopes for home ownership, health insurance, or venture funding are dying in a 50 millisecond AI decision.

AI is making decisions about whether you get into a university. Economists have demonstrated the powerful impact that a university education has on economic mobility at all levels of society. Driven by findings like these I founded my first startup, an EdTech company, to end high-stakes testing. I knew that standardized testing poorly predicted student performance. Using machine learning, we were able to turn everyday interactions between students and instructors (such as discussion forums or conversations in the classroom) into rich insights about their comprehension. We ran experiments with kindergarteners and college students demonstrating that these naturalistic data points gave instructors a more accurate look at their students’ progress than traditional testing.

AI isn’t inherently evil; but AI that acts only in the interest of others can never truly act in yours.

I remain passionate about using machine learning to transform education, but I discovered that almost every technology is inequality increasing because the people who need it the least are the best able to make use of it2. Twenty years of working with machine learning has also taught me that AI cannot magically find solutions to problems that we don’t truly understand ourselves. In an effort to advance inclusion, many universities are experimenting with proprietary machine learning systems to handle admissions and student assessment. Yet if universities today already fail to determine which potential students will go on to have the biggest impact on the world, AI is hardly the tool to recognize them. When an opaque AI optimizes its admissions criteria by reducing the number of female students, or those of color, there may be no trail of evidence for appeal. AI isn’t inherently evil; but AI that acts only in the interest of others can never truly act in yours.

*Accountability is not a one-sided activity: it exists between two or more parties, each empowered to enforce. *

Plutocratic AI steals our voices. The only way forward is a balance of powers that cannot be accomplished through the unilateral self-regulation of those controlling AI. Accountability is not a one-sided activity: it exists between two or more parties, each empowered to enforce. AI needs a new social contract, a constitution, between AI plutocrats and individual citizens. Laws managing data ownership miss the point; they become transient barriers around which the economy eventually flows. If we intend to protect individual liberty, then individuals must be empowered.

Some thought leaders envision kids on deserted islands using smartphones to run machine learning models on Amazon EC2 instances, but I built five AI-driven companies; I built an AI to treat my son’s diabetes; I built an AI to read and analyze the notes that I’m using to write this article. When it comes to machine learning, I am as empowered as it is possible to be, and I don’t know what sort of desert island kids these people are imagining. It is as irrational to place the onus on you to build your own protections against the rapacious use of AI as it is to expect you to defend yourself in court or diagnose your own cancer. If you’re expected to develop an AI protector that can navigate the world and defend you against abuses of power, then that's your whole job. I build AI for a living and even I can’t fully protect myself and my family alone.

The AI Plutocracy Needs a Balance of Powers

AI can do wonderful things. We have a right to AI in our lives, but civil rights can’t exist in a world of hidden calculations. A civil right with no redress mechanism is no civil right at all. AI needs a constitution. More accurately, we need a constitution that defines access to artificial intelligence acting solely on our behalf as a civil right. We have the right to AI that acts exclusively in our self-interest, not someone else's, the same way that we have the right to a lawyer, the right to a court date, an impartial judge, and judicial review. We have the right to dynamic institutions working to protect us. We have the right to participate in the security of our own data. Three proposals that directly address this balance of power are data audits, “Fringe Divisions”, and data trusts.

If AI decides who gets loans and jobs, open the books on how it’s done

No, not in a million years could I imagine any big tech company willingly opening their databases to inspection by a third party. Yet we have come to expect exactly this form of financial transparency in public companies via audits. If our goal was to give all of the guidelines, manifestos, checklists, and laws some tangible teeth, those teeth would be in the form of data audits. Any company collecting data and making use of machine learning should agree to third party audits of their data content and practices just as they would with their finances. If AI decides who gets loans and jobs, open the books on how it’s done. This would be one small positive step towards a return of our collective agency. (Again, kicking and screaming is the only way I see the tech industry entering this future.)

Data audits allow for insight; action still requires agency. Imagine knowing that an Ebola outbreak was taking place but having no World Health Organization or Center for Disease Control to actively fight it. These institutions represent our collective agency in dedicating true expertise to our collective wellbeing. We might then imagine a World Data Organization or a Center for AI Control bringing the same level of expertise and collective action to fight the rapacious use of AI. While you may not have the infrastructure or time to combat every AI-driven violation of your civil rights, we might build a diversity of organizations–governmental, transnational, NGO–that specialize in fighting these outbreaks. (If you still aren’t getting it, just imagine Fringe Division but with AI cows. And if you are getting that, you’re a fucking nerd.)

Of course to be experts, these Fringe Divisions would need to be passionate about AI. Some ponderous bureaucracy simply meant to impede life-saving innovation would never be able to do the job of tracking bleeding-edge AI research. A multitude of such institutions, representing diverse stakeholders, could help balance the political equation.

Important as they may be, though, neither data audits nor Fringe Divisions directly empower individuals. The concept of data trusts, however, could be just such a radical transformation.

Historically, trusts are legal entities that act in the interest of trust members to hold and make decisions about assets such as property or investments. A data trust takes and substantially extends this concept. Not only do they provide member-defined standards for storing and sharing data, but they can go even further by providing the infrastructure and algorithms necessary to support civil AI, artificial intelligence acting exclusively in your self interest.

Many libertarian economists and glassy-eyed entrepreneurs suggest that your data is not worth anything to you. They argue that if you give open access to companies like Google and Facebook, they will in turn give you something back, often with a price tag attached. This traps us in a mercantile relationship with big AI organizations. They rapaciously consume your supposedly valueless raw data and sell it back to you in revenue-maximizing monetization schemes. Data trusts ensure that you are no longer acting alone: “you” becomes “we” as the trust’s infrastructure actively protects our rights not just to privacy but to the fundamentals of work, education, and judicial review.

Data trusts can and should come in diverse forms, representing the many different standards by which individual communities wish to govern their relationship with artificial intelligence and the broader digital world. They serve as an interface between companies, the government, and whomever else might be watching you. One trust might militantly lock down all access to data, protecting users from all comers, while another might have specialized policies (i.e. differential privacy) for interacting with medical AIs. For those that want to share their data without any restrictions and reap as many “free” services as possible, there are trusts out there for you. Beyond simply defining rules about data sharing, however, the most valuable trusts will actively develop AI to promote the interests of its members and balance the political scale.

The deepest and most constitutionally-protected parts of our lives–jobs, loans, prices, education, justice, and so much more–are threatened not by AI’s failures but by its concentration of power. Global scale AI depends on access to data, talent, and massive infrastructure. This is almost entirely controlled by a tiny number of companies and countries, serving their interests, instead of yours. Searching for a job? AI recruiting serves the employers. Dreaming of a home? AI finance serves the bank.

AI must serve you. While data audits and institutions can broadly balance the political equation, data trusts can actively search for the perfect job, the best terms for a loan, or the right scholarship. In an AI-driven world, civil rights are only meaningful when individuals have AI directly serving on their side of these digital relationships.

To be successful, data trusts must overcome the monopolies on data, talent, and infrastructure that are at the heart of plutocratic AI. They solve the data problem by their very nature. While infrastructure represents a daunting barrier demanding commitment from policy makers and the public, talent is surprisingly abundant. Enormous numbers of brilliant individuals working at universities, NGOs, and even independently, share cutting-edge machine learning research and algorithms with the world. In fact, many of our projects at Socos Labs, the Mad Science incubator I co-founded, serve exactly this purpose.

...a civil right which you have no means to exercise is no right at all...

And when you’re at your most vulnerable, your AI can help make you more than just a victim. For example, AI can track your rape kit. Tens of thousands of untested rape kits collect dust in evidence lockers all over the country. The victims assume that all of these kits are being tested, but many police departments have historically undervalued pursuing these cases. You might never know. Just as in being passed over for a job or a loan, a civil right which you have no means to exercise is no right at all, including your right to protection by the police.

The details of police investigations are understandably hidden from the public and often from the victims themselves. The problem is that this makes it impossible for an individual to know whether their case is being pursued, whether their rape kit is sitting ignored on some shelf. In collaboration with groups like the Stanford Journalism project Big Local News, Socos Labs has looked at how public records around policing and prosecution can inform our understanding of good and bad practices around the country. While you may not know whether your specific rape kit has been sent out, your AI can make a pretty damn good guess by tracking indictments and prosecutions in your local community. Your AI becomes the mechanism with which you exert your civil right.

AI needs a constitution. Socos is just one company; the actions of lone groups and individuals won’t create the deeper change we need. We need to look at the balance of power. The tiny gang that holds all the power–the AI plutocracy–needn’t do anything malicious for this power-imbalance to be unsustainable. We can’t have civil rights until that changes.

Policymakers: you have a crucial role in enacting actual laws–or even a constitutional amendment–that addresses the incredible centrality of data and machine learning in modern civil rights. It is your responsibility to establish policies that don’t just make Fringe Divisions and data trusts an aspiration but make them a reality. None of our suggestions are viable without your commitment to protect the rights of your neighbors.

The WHO and the CDC combat disease hotspots around the world; the Fed fights instabilities in our economy. These organizations provide a model to policymakers on how Fringe Divisions can confront AI hotspots and instabilities. For example, Fringe Divisions need the kind of expertise and technical resources embodied in institutions like the CDC, but they can also leverage positive regulatory power like the Fed by redirecting data access and research funding towards more prosocial applications.

Data trusts are more complicated. Their three necessary ingredients are data, talent, and infrastructure. As we described above, data trusts generate their own data by the very nature of their membership and can access a broad range of talent. Policymakers, however, must play a role in securing the necessary infrastructure for data trusts to be more than an elite fantasy. The highly specialized infrastructure needed to run global-scale AI is the privilege of the AI plutocracy. Without access to AWS, Microsoft Azure, or Alibaba Cloud, data trusts would not be able to operate at scale. Policymakers must tackle the specialized laws that carve out and fund the infrastructure for these trusts to function.

For many of the tech companies that have built on this AI infrastructure, the idea of government involvement might sound terrifying. But, corporate officers, you have a role here as well. You must move away from the techno-utopian idealism of assuming that good intentions will solve problems. Self-regulation, advisory boards, and ethics guidelines are all well intended but do not solve the problems that we have described. If, as some have said, “AI is the new oil,” then much like Rockefeller, you are leading us into a Gilded Age of AI plutocracy. But that age also gave rise to the audit, not because of government intervention or legal obligations, but because transparency drove growth. You are in a position to modernize our data markets just as financial markets were modernized in previous ages. Institutional investors, from pension funds to family offices, will begin to pull their money out of companies that refuse.

And you, fellow citizen–you who’ve missed out on jobs, loans, promotions, and court rulings because AI served only the other side–the simple truth is that we have no easy call to action for you. We could say, “be more thoughtful about your data; go learn how to build AI,” but expecting millions of Americans to quit their jobs, become experts in machine learning, and fight the man behind the machine is foolish. It’s as realistic as a kid on a deserted island spinning up an EC2 instance and building an AI with nothing but a smartphone. There are no data trusts for you to join today. Only the most nascent Fringe Divisions hunt for AI hotspots. No company is allowing independent audits of how it is using your data. Every policy paper suggesting that this is your fault for not being sufficiently careful hides the real problem: the AI plutocracy is gathering all the power.

Scientists and entrepreneurs often think they're superhuman. (In fact, most Silicon Valley founders think they are a hero in an Ayn Rand novel, which is even more terrifying.) They’re not. They’re just like all the rest of us, and I'm just like the rest of you. If you trust me arbitrarily, I will eventually choose to do the right thing for me, not you. This isn’t because I'm a bad person but because any system without a balance of power is simply unsustainable. AI needs a constitution–it’s on us to write it. It’s the only thing we can do.