Sexyface

In 2009 I founded my first startup, Augniscient, using cutting-edge machine learning and groundbreaking cognitive models to do what any aspiring, adventurous, heroic, world-disrupting Silicon Valley entrepreneur could hope to do: create an incredibly sleazy game for the horny masses. It was the heyday of tech–in the age of Zynga and Farmville, everyone’s goal was to grab as much money as quickly and cheaply as possible. Armed with PhDs in theoretical neuroscience and psychology, I spent all of my time in front of my computer perfecting the algorithm that was going to power a messy kind of love. While the other brilliant minds in Silicon Valley were busily growth-hacking high-burn social startups to disintermediate people, I was doing something different, something that could actually have a lasting impact on the world: I was helping people get laid. The game was called SexyFace, and the premise was simple. For free, we would use the cutting edge of artificial intelligence to find everyone on Facebook that you thought was sexy. And for five dollars, we’d find everyone that thought you were sexy.

While I was clearly making all the right choices in life, an orphaned nine-year-old girl was fleeing Afghanistan and crossing into Pakistan in a caravan of refugees. Dizzy from dehydration, knees weak with exhaustion, she focused on reaching wherever the caravan would take her. She knew nothing of the camp they were headed towards, and when she finally arrived, the line to enter continued for miles. The sun beat down from above, raising temperatures to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. There was no shade and the smell of human waste hung in the air, burning her nostrils. When she reached the front of the line, she looked up to see a strange-looking man staring into her face. She recoiled, but he passed her a cup of water. She gulped it down eagerly, the water streaking the dust across her mouth and chin. The man knelt down next to her and lifted a large camera to his eye. Terrified, the little girl gripped the cup to her chest as the photographer snapped a shot of her face, exhausted, dirt-stained, and lost.

Unaccompanied and with no family to protect her, she worked in the camp, a lost orphan carrying water, cleaning tents, and scrubbing clothes. The unrelenting stress of these early years became toxic to her body and her mind. She suffered from depression and PTSD, but there was no trauma counseling in the camp and no medical treatment. Later, the refugee leaders in the camp forced her into a “sale” marriage to a man who was cruel and violent. The accumulated stress and poverty wore away her cognitive control and emotion regulation. She had three children before she was sixteen, and just as her husband beat her, she beat her children. By twenty, she had had no formal education, a life spent entirely in a camp. Only one face in a sea of lost children, she envisioned killing herself every day.

If only her customer lifetime value were higher a VC might have funded an app to democratize her education. But in other news, SexyFace worked astonishingly well. The game would show a bunch of faces, male and female, young and old, from around the world, and ask players, “Who’s sexy?” With each selection, the AI driving the game would probe the borders of the player’s kinks, until after just a few rounds, it had it down. You didn’t even need to know what “sexy” meant to you in order to play–the damn game would figure it out! South Asian male with muttonchops and a sense of ennui? As long as you were consistent in your judgments and there were enough positive examples in the dataset (i.e., everything we could pull off of Flickr and Facebook) it would find all the other faces that tickled your fancy (and maybe tickled a whole lot more). Got a Costanza-esque thing for a pinkish hue? SexyFace has your pinkish dream. Does competence in a partner drop your knickers? SexyFace has you covered. (Got a foot thing...well, we did think about doing SexyFoot at one time, but I kind of suspected that the necessary training data couldn’t be found. I was horrifically wrong and can never unknow that truth.) Whatever your kink, Sexyface would find that pinkish, South Asian foot with a sense of ennui for you.

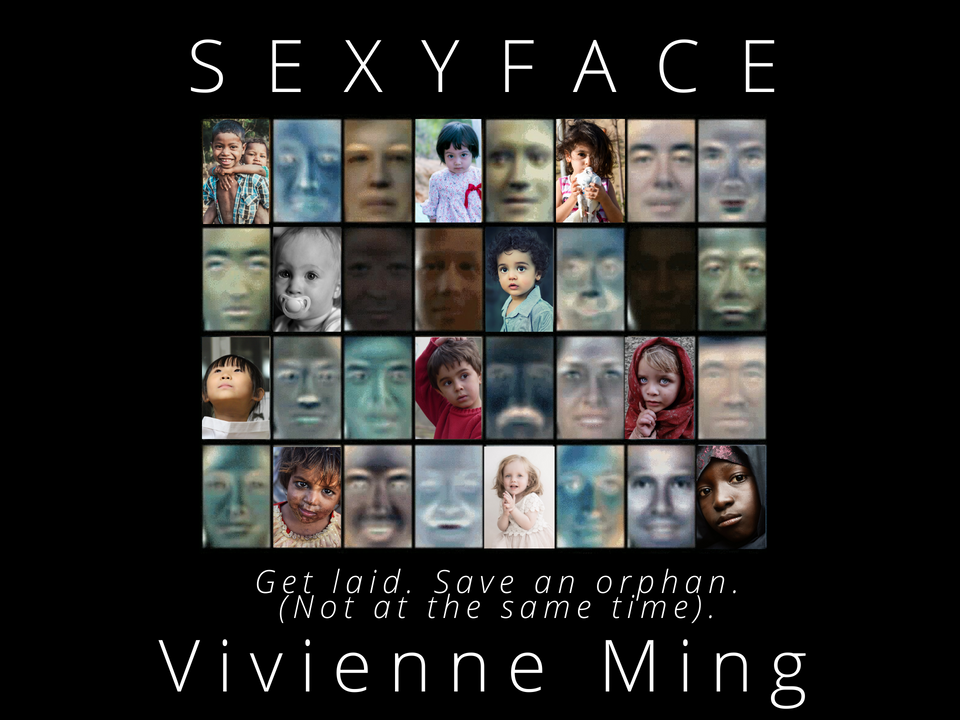

The bottom line: SexyFace was radical–an engineering dream. It was another of the many projects inspired by my CIA-funded research building a real-time lie detection system for faces. (Admit it, that’s cool, right?) A deep neural network powered SexyFace by learning a “language” of faces, not just the physical features but the intangible quality of players’ preferences. What you see in the image below is a tiny number of words in that language. None of these faces are actual people. Even the face-words that look the most like actual people (such as the face in the upper-left corner) didn’t represent any real person in the database. We called them “anchor faces”: prototypical faces that were then nuanced and modified by the other words. By combining these anchor faces with other face-words acting as adjectives and verbs you could create any face. In total, the language had thousands of words, and SexyFace “perceived” any specific face as a unique sentence written from a small set of face-words. When the player selected a cocky East Asian man with a big mustache and glasses, the AI inside the game saw it as face-word A4 + C5 + a complex set of non-linear weights across other words (that last coding for cocky).

So, essentially, we made this amazing program that could do things like help autistic kids read facial expressions or analyze how the very faces of business leaders drive the gender wage gap. Hell, we could even go beyond faces and apply the algorithm to the learning experiences of young students with the goal of ending all high-stakes testing. But none of those lame ideas would make any money. What’s more exciting for VC funders than AI-powered software ready to make your kinky dreams come true?

And SexyFace could do much more than find attractive people. The deep density component model I developed for SexyFace could guess any face category, not just “sexy”. Try asking someone why a face is “competent” or how they perceive gender or happiness. They might answer you honestly, but those answers often don’t reflect how they actually made the decision. Inside the SexyFace model, we could see what drove them. For example, smiling faces were perceived as more feminine; the presence of glasses increased white people’s perception of “Asian-ness”. No one would define gender or race in terms of smiles or glasses, but in the wild recesses of our own minds, we clearly do.

SexyFace could read your subconscious mind. (I love the whole “read your mind” pitch; it’s a great way to sell AI to rubes.) Just think of the implications. No need for relationships. No need for personality. None of the time-consuming mess of cyber-stalking. Get laid now. Needless to say, SexyFace was going to make me rich while the world benefited from my genius–surely the very definition of doing well by doing good.

Meanwhile[1], civil war was breaking out in Rwanda. Fleeing from his own neighbors, a ten-year-old boy crossed into Western Tanzania along with half a million other refugees. When they reached the camp, the army had already taken over, militarizing the camp leaders and forcefully recruiting refugees, including children. Frightened and already suffering from severe PTSD and anxiety, the little boy lost his ability to speak and withdrew from contact, hiding for days and then weeks inside a trash can on the camp’s outskirts. At night, he relived memories of his parents’ murder: rebels herding the people of his town into a classroom at his school and then returning to massacre them. Alone in the camp with nothing but these memories, he developed a sleep disorder and awoke frequently from the inability to control his bladder or bowels. A rebel attack on the camp destroyed the camp’s scarce food and water resources, driving away the volunteers who had tried unsuccessfully to run a childcare center for orphaned children like him. The boy had no one. Robbed of his own potential, his working memory, and cognitive function, the rest of his life was defined by the trauma he experienced at that camp. The only record of the boy’s existence was a photograph taken by a volunteer from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees who, just before evacuating the camp, snapped a picture of the little boy’s anxious face.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, the point of SexyFace wasn’t actually to help people find hookups, and I’m not a horrible person[2]. The UN has a book with over a million photographs of orphaned refugees in camps around the world. The reason the game existed, from the very beginning, was to train a machine learning system to understand how we perceive the faces in those photographs and reunite orphans refugees with their extended families. AI can do good if that’s how we choose to use it.

The model behind SexyFace was initially used for an education project at my first company, Augniscient[3]. We’d built a system that could track students’ conceptual learning from free-form discussions, but I needed a more grounded demonstration of the algorithm for VCs. Having worked on face recognition models in the past, I built a version of the “mind-reading” face game using photos from Facebook and Flickr to prove that this technology could learn in real-time. After a few rounds of playing, the VCs saw how the algorithm could get inside students’ heads.

What we hoped to do was end high-stakes testing: no more finals or midterms, no more SATs or GREs. Using the model that powered SexyFace, we wanted to replace those tests entirely. Instead, we would use our AI to observe students’ actual learning experiences. Listening to them chat with each other online, we could out-perform the final exam early enough for the teachers to act. In the end, we would be able to replace those biased tests entirely with “personalized” insights about each student.

Then one day we got a call from Ericsson. The multinational company ran a Technology for Good program and was partnering with the UN and Columbia University on the Millennium Cities Initiative. They’d heard about our work at Augniscient and wanted to meet. When they saw the SexyFace demo, the topic quickly shifted away from education to refugees. Ericsson was also supporting Refugees United, a program to reunite the one million orphans in refugee camps around the world with their extended family members. Through SexyFace, we made a real game that was also a trojan: just by playing, horny twenty-somethings helped train the AI to recognize lost kids.

You are living in Damascus and haven’t heard from your sister's family in Aleppo in weeks. You spend your nights ceaselessly watching CNN’s reporting on what you’ve lived firsthand: the crisis in Syria has left more than 13 million people in need of humanitarian assistance, almost six million of them children. As you watch, you desperately hope that your niece’s picture doesn’t appear among those shot or drowned. During the day you travel to refugee camps on the border with Jordan, looking for your sister and her daughter, but there is no record of their names. Instead, the UN gives you a book. It’s filled with photographs of all the Syrian orphan refugees in camps in the region. You begin searching, page after page, hoping not to miss that moment when the photo of your niece’s frightened face passes by.

On your next visit, the UN hands you a tablet instead of that book. They explain that if you can select a few faces that look most like your niece, it might help them find her faster. So you pick two kids from the first group of images, then two more from the next. It only takes a few minutes, and there she is. After weeks of searching, you find your niece. Unfortunately, because you found her, you know that she’s alone. Your sister is lost. At the very least, your niece is coming home with you. She won’t spend decades living in the camp like so many other children of her generation. She’ll know what it means to live in a home with a family that cares for her. The cognitive shortcomings and health problems she could have faced during the crisis will be minimized. She will be educated and possibly raise a healthy family of her own someday. So much of who she could be is given back to her. That was the whole purpose of SexyFace.

And that is what AI can do. Big, scary technologies don’t have to be big and scary; we can choose to use AI for good in the world.

So, we saved the day. We changed lives and made a difference. Each of these stories has a happy ending, because we used our technology for a greater good...that’s where you thought this story was going, right? I really wish it were true. I had the opportunity to help. I could have made a difference, but I got scared.

You’d be scared too. We were an unfunded startup trying to advance education, but VCs saw education as an indulgence. We were getting pushed towards mundane projects with solid revenue[4]. I was spending all my time working on this philanthropic project while we struggled to find any funding for Augniscient’s test-taking reform. I had rent to pay. I had a new baby to care for. Surely our startup could not simply donate all of its time and technology, no matter how important the cause. It felt grown-up to say “no”. (As they say in business, “no” is the foundation of great entrepreneurs. Some even call it an artform.) But we weren’t grown up, we just ran out of courage. We had the choice to do the right thing and we failed.

Saying no to the Ericsson team was one of the worst mistakes of my career. Months later, I reached back out to their company’s Technology for Good team. We had completely rebuilt SexyFace and wanted to help. But the moment had passed, and SexyFace was never put to use. Ericsson’s partnership with Refugees United did end up saving many lives, but had we participated, we could have saved so many more. That fact is something I will never forget. I’m still as proud of SexyFace as anything I’ve ever done and I’ll never say no again. I should have made a personal sacrifice; instead I made a soul sacrifice.

AI is simply a tool; it is only good or bad because of what we choose to do with it. This story isn’t really about technology; it’s about the hard lessons I learned from my personal failure in the face of that technology. Now, I urge everyone: don’t wait until later to do good, until after you’ve “made it”. SexyFace is one of the biggest regrets of my life, and I will not repeat it. Be courageous. Do good now and whenever possible. Start tonight.

[1] Well, not exactly “meanwhile back at the ranch”. The Rwandan Genocide was more than a decade past by the time I launched Augniscient.

[2] I hope, though many might disagree for unrelated reasons.

[3] And no, getting people laid was never actually part of the company’s business model.

[4] Unstructured log file analysis, anyone? How’s that for sexy!