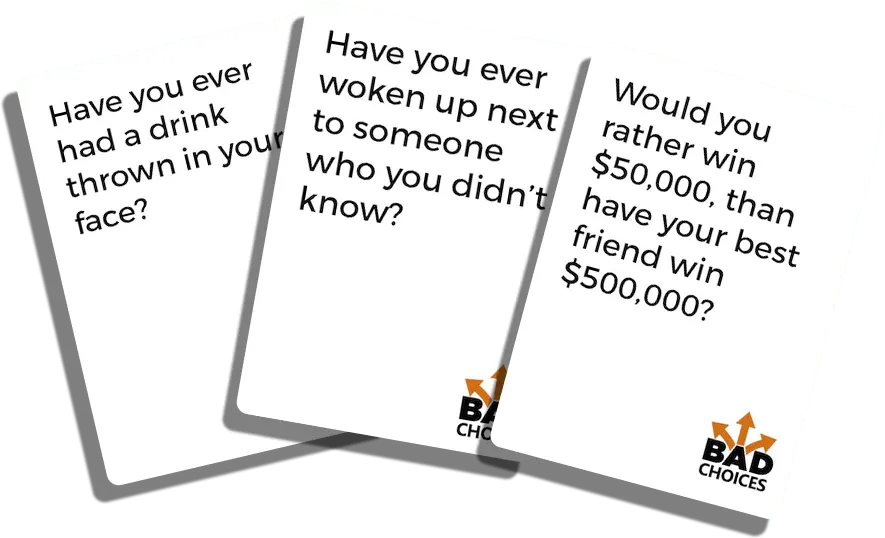

The Economics of Bad Choices

This week's Socos Academy looks at various bad choices.

Mad Science Solves...

Indulge me this week. Read my Research Roundup below and then let’s meet again at the bottom of the newsletter to talk about subject utility.

Stage & Screen

Most of what I shared last week is still true so...cut & paste:

LONDON (November 13-17): Hey UK, I'm coming your way! And it's not just London this time.

- I'm speaking at the University of Birmingham on the 14th. (link to come)

- I'll be giving a keynote for the FT's Future of AI on the 16th. Buy your ticket now!

- And I'm even flying up for the Aberdeen Tech Fest with my keynote on the 17th.

New York City (November 30 - December 7): Then in December I'm back in NYC on my endless quest to find the fabled best slice.

- I'm talking "AI, Ethics, and Investments" for RFK Human Rights on the 30th.

- (I'll be doing a remote keynote for the UK on the 4th: Developing Excellence in Medical Education.)

- We cogitating over the future of healthcare with the new ARPA-H on the 5th.

- And I'll be at the RFK Ripple of Hope Gala on the 6th!

I still have open times in both London and NYC. I would love to give a talk just for your organization on any topic: AI, neurotech, education, the Future of Creativity, the Neuroscience of Trust, The Tax on Being Different ...why I'm such a charming weirdo. If you have events, opportunities, or would be interested in hosting a dinner or other event, please reach out to my team below.

Research Roundup

Unprotected Left Turns

Back in the 90s, I developed my first pet economic indicator: artisanal soda shelfspace. The more the economy overheats, the more shelfspace at local markets is devoted to overpriced, handcrafted sodas with ironic labels. Like all pet indicators, it’s not a causal mechanism or validated correlate; it's just a rule of thumb that plays on your own internal models of the world, in this case

- Consumers have enough money that a $10 soda feels like a staple.

- Families feel secure enough in their finances that one of them pursuing their…dream(?) job handcrafting soda seems like a reasonable career.

- There is so much unproductive investment money floating around that it seems rational to fund (1) and (2).

As a consumer of those same sodas, I’m thrilled that so many bad choices were made in the 90’s, but come the DotCom bust, those shelves were strictly Coke and Bud. And when I see 79 different brands of kombucha, yogurt tonics, and hemp infusions on the shelves today, I just shake my head and grab my kombucha.

Today I have a new pet economic indicator: unprotected left turns (ULT). As I travel around California and the rest of the US, I make a special note of how many cars are waiting to make unprotected left turns across busy traffic at rush hour. (If you live in the UK, feel free to substitute “unprotected right turn”.) My prediction is that communities with higher rates of ULT show worse economic and broader human development. Irrational and unfair? I’m not assuming that every frustrated driver praying for a break in traffic is a bad person, but a substantial number of them make this turn every day as a part of their commute. They know the traffic will be there, and on some level they know the even more profound truth that an intersection with a light or traffic circle is no more than a block or two away. And yet they wait at that unprotected turn every morning, ignoring the better but less immediate choice.

To me this has always felt like a population-level natural experiment in executive control. The more ULTs, the lower the local levels of executive control, which in turn undermines economic development.

Am I unfair? Is my pet indicator just simply wrong? Maybe, but some recent research suggests that “patience” and “time preferences” tell important stories about communities. One study used “social-media data – Facebook interests – to construct novel regional measures of patience within Italy and the United States”. They found that regional differences in patience were “strongly positively associated with student achievement” and accounted for “2/3 of the achievement variation across Italian regions and ⅓ across U.S. states”.

The other study found that individuals that are “present-focused” made poorer food choices, finding both “self-control problems” and “important aspects of nutrition are driven by time preferences”. I see some of those present-focused individuals waiting at unprotected left turns every day.

I’m curious how both of these measures interrelate with standard measures of working memory, executive control, resilience, and other meta-learning factors. More importantly, what interventions can increase patience and “future-focus”?

MBA Lift

Is an MBA worth the time and money? It’s a question that’s often asked but hard to answer. Attending an elite program highly correlates with elite career outcomes, but those students would almost certainly have had exceptional outcomes no matter how they spent those years. What really matters?

Given that the average cost of an MBA in the US is $225,605, let’s start by understanding why students choose to attend. That cost is a huge factor for the majority of prospective MBA students, but with nearly all surveyed recruiters claiming that the demand for MBAs will hold or increase, an MBA might feel like a requirement. (BTW - I interpret that recruiter statistic largely as, “I plan to look for a prestigious MBA on their resume so I don’t have to dig deeper.”)

Is it worth it? 85% of MBA graduates between 2010 and 2021 think so. What did they get for the money and opportunity cost? The most common responses are

- “increased employability”

- “greater earning power”

- “broader professional network”

So…actually learning something doesn’t factor into the choice to attend school. I realize that PhD and MBA students are very different people, but it is striking to me that none of the cited motivations reflect any intrinsic value to an MBA. While surely there must be some who see value in MBA scholarship, this disconnect between motivations—doing one thing because you actually want to do another—might be a source of bad outcomes for many MBA graduates.

Self-reported career outcomes suggest value: the majority of graduates report advancing “one job level” post MBA, particularly those in lower-level positions. But self-reported returns for “Black, Hispanic and Native American graduates” were significantly lower than for other groups. And of course, there’s always that question: would their career have advanced as much in 2 years without the MBA?

If we look at the schools granting “vast majority” of MBAs—”for-profit, online, and regional universities”—the answer is a clear no. Graduates from these schools received job offers at the same rate as applicants without MBAs, “even for positions that listed a preference for a master's degree”. And this effect was even worse for Black men; they received “30% fewer positive responses than otherwise equivalent applicants”.

Way back in 2014, I developed an analysis technique to rank global universities on how a degree from them predicts career outcomes by the holder. I was genuinely shocked to find that the bottom two-thirds of universities on our list were negative predictors of career outcomes for its graduates. The students would have been better off never earning a degree at all. And while the quality of these “schools” is obviously part of the problem, the motivations of the students clearly plays a role. Treating MBAs, or any degree, as a magic ticket to wealth without any intrinsic value guarantees a market for false dreams and snake oil.

Back to my rambling on the economics of bad choices:

Many in economics treat “choice” as a magical process that reveals preferences and maximizes welfare. If targeted ads using personal information induce you to buy more, then the use of personal information must be welfare maximizing, regardless of whether those additional products add any meaningful value into your life. If you choose to use a payday lender, then assuming you are capable of otherwise rational decisions, payday lenders must be a welfare-increasing feature of the economy. If you refuse to give up Facebook (or TikTok or Instagram) for less than $1000, then you have revealed the true value of these social products. Taken to its extreme, you choose to be wealthy or healthy or beautiful, and if you aren’t…well that was your choice.

As explored in the research above, however, people regularly make “choices” that are demonstrably welfare reducing. I wasn’t surprised to see that most MBAs have little positive effects on career outcomes (contradicting the highly personalized ad targeting used buy the largest for profit vendors) because years ago I developed a model of the value add of thousands of global universities on working professionals’ career outcomes. The bottom 2/3s of schools in our analysis were negative predictors, implying that those graduates would have been better off just going straight into the job market rather than spending the tuition and years of study.

Beyond the question of choice and welfare, there is also the naive notion that people’s choices are stable over contexts. In contrast to studies showing that individuals must be paid hundreds of dollars to leave social media, other studies show that similar populations forced to leave social media must be paid to return. Essentially the same people make directly conflicting “choices” under differing contexts. What are preferences in a world dominated by hysteresis? (Elasticity does mean opposing decisions from the same people.)

And those payday lender studies about the welfare value of usury? An enormous number of the highly rational participants in those studies—regular payday lending customers that show accurate judgements about their personal economic circumstances—failed to use the $250 gift cards given them in exchange for their participation. Hardly a rational choice, but this behavior reveals how profoundly context can influence individual choice.

In a very different study, before the start of an experiment on prosocial collaboration, nearly all participants correctly identified that they need to collaborate with participants most dissimilar to themselves in order to maximize the dollars earned. But as soon as the collaboration phase began, nearly everyone chose to collaborate with ingroup members rather than outgroup, reducing their earnings. Most fascinating, the participants then presented post hoc explanations of why they were wrong and needed to change strategy, even though their pre-experiment selves were right.

All of this is evidence of a phenomenon of subjective utility, where the neural underpinnings of decisions are in conflict between the explicit rational abstractions of utility and the implicit lived experience of a choice’s utility. Even if you know that a better choice exists in the abstract, if you’ve never experienced its benefits, never known anyone who has, the implicit system will diverge from the idealized explicit abstraction. And as cognitive load increases, as marketer’s vie for attention and contexts drains emotional resilience, the implicit system slowly overwhelms the explicit. The results...reality television (and so much else).

Choice isn’t a magic wand that explains every global phenomenon as a simple function of individual preferences. In fact, not just opportunity but choice itself is fundamentally inequitably distributed. Rather than treating people’s choices as revealing welfare and preference—choices made under cognitive and emotional load, under the assault of a trillion dollar industry vying for your attention, targeted in moments of weakness rather than strength—let’s focus on building a generation of people better able to make effortful choices of lasting value.

| Follow more of my work at | |

|---|---|

| Socos Labs | The Human Trust |

| Dionysus Health | Optoceutics |

| RFK Human Rights | GenderCool |

| Crisis Venture Studios | Inclusion Impact Index |

| Neurotech Collider Hub at UC Berkeley |