The Rise and Fall of Bad People

This week's Socos Academy looks at schadenfreude, cynicism, and the burden of great men.

Mad Science Solves...

When I read newspapers call OpenAI “the Cradle of AI”, a la the Rift Valley, or refer to Sam Altman as “the AI whisperer”, it is hard to not feel schadenfreude at the chaos they experienced last week. It’s even harder to not feel sour grapes (those Germans have a word for everything) at Altman’s triumphant return. (Just a couple of years ago it was “Elon Musk’s OpenAI”, and all I could think was how much it diminished the hard work of so many actual AI engineers and researchers.)

What drives these feelings isn’t some personal animus. I’ve never met Altman, and Musk only in literal passing. Instead it is the determined way in which they’ve centered themselves in stories that are so much bigger than one person. They have turned grand societal ambitions—inhabiting space, slowing climate change, birthing superintelligence—into personal stories of power, greed, and self-aggrandizement.

I know that many devotees of Rand and Nietzsche might see self-interest as fundamental to great works, but it is hard to reconcile these great man theories, particularly great man theories devoid of humility and sacrifice, with my own research on purpose. The psychological construct purpose is some cause that holders view as bigger than themselves and will take more than a lifetime to complete. It is a cause worthy of sacrifice. The ambitions of Musk and Altman could certainly fit this definition except that both men (and many other self-appointed saviors) seem to see themselves as bigger than their purpose. They are great men that deserve a little something extra for their efforts. (To be fair, I saw the same thing among many neoliberal Democrats in the 90s.)

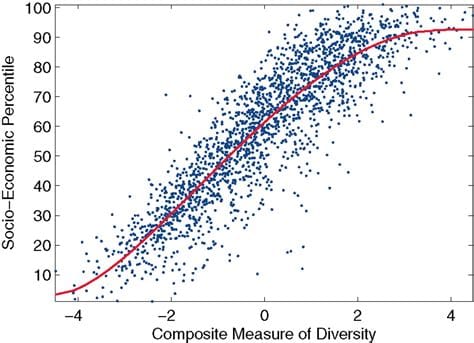

In contrast, my research suggests that those who score high on strength of purpose, despite their self-sacrifice and seemingly diminished self-interest, lead better lives along almost every dimension: wealth, health, and happiness. While it’s pointless disputing the wealth of Musk or Peter Thiel, their ambitions ultimately depend on the communities built to achieve them. One of the reasons people with greater strength of purpose lead better lives is that their sacrifices are a signal to the community (or if you prefer, to the market) around which otherwise suspicious, self-interested members can coordinate their actions. Put simply: humility enhances coordination. And when it is absent, the great men might find a measure of relative greatness, but the community is tangibly diminished.

Stage & Screen

New York City, here I come...twice! (Nov 30 - Dec 1 & Dec 4-7)

- On the 30th

- I'm talking "AI, Ethics, and Investments" for RFK Human Rights.

- Then, Building better AI by Investing in People remotely for for Singapore and Manila.

- On the 4th

- I'll explore how AI will impact medical education for Developing Excellence in Medical Education.

- Then a panel for Breton Woods Revisited

- And finally a discussion on AI, Design, and Ethnography.

- on the 5th I'll be cogitating over the future of healthcare with the new ARPA-H.

- And I'll be at the RFK Ripple of Hope Gala on the 6th!

I still have open times in NYC. I would love to give a talk just for your organization on any topic: AI, neurotech, education, the Future of Creativity, the Neuroscience of Trust, The Tax on Being Different ...why I'm such a charming weirdo. If you have events, opportunities, or would be interested in hosting a dinner or other event, please reach out to my team below.

Research Roundup

Why do we let them?

I’ve never been mystified by the appeal of populist philosophies and leaders—simple answers violently delivered against undeniable villains. It's the very appeal of some of my favorite movies and fantasy novels. But the real world is messy, and true villains are few and far between (though some of those very populist leaders, from across the political spectrum, are the best candidates…for villainy, not public office.)

Sometimes I wonder, though, am I just not seeing the simple truth of the world. In moments like these I am heartened when researchers answer profoundly important questions in a straight-forward way. Tracking the impact of “51 populist presidents and prime ministers from 1900 to 2020” reveals that 15 years after their rise to power, “GDP per capita is 10% lower” than “a plausible non-populist counterfactual”, i.e. a world in which they’d never come to power. These populists fracture economies, increase economic instability, and erode institutions, all of which worsens the lives of their citizens.

Populists promise a better world but steal from our future. Why do we believe the promises of the people least likely to keep them? One factor (of many) is that we “tend to believe in cynical individuals' cognitive superiority”, despite the reality that “cynical…individuals generally do worse on cognitive ability and academic competency tasks”. Component individuals recognize the messiness of the world and hold “contingent attitudes” in case they are wrong. “Less competent individuals embraced cynicism unconditionally.” (Such as claiming you weren’t boorishly vaping during a theater performance in a world with ubiquitous video surveillance.)

The authors of the study suggest that ”at low levels of competence holding a cynical worldview might represent an adaptive default strategy to avoid the potential costs of falling prey to others' cunning”. And yet this cynicism makes us even more susceptible to the very grifters selling poison as societal medicine.

Schadenfreude

“Schadenfreude is the distinctive pleasure people derive from others' misfortune.”

For some people (me), it feels so good it’s scary. And so I was intrigued to discover that someone has an entire research program around schadenfreude. They theorize that it has “three separable but interrelated subforms (aggression, rivalry, and justice)” that are elicited and integrated by “dehumanization”. So far this seems to capture my feelings about…a great many people.

Delving into the brain, feelings of envy came with increased ACC activity, while schadenfreude increased with ventral striatum (VS) activation when “misfortunes happened to envied persons”. So, when bad things happen to “bad” people, my ACC whispers the gossip to my ventral striatum, who then villainously sprinkles dopamine and endogenous opioids all over my useless moralizing.

All of this apparently makes me not unlike patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). Their deficits in social cognition and inhibitory control correlate with experiences of envy (ACC) and schadenfreude (VS). This population also reveals that the underlying sense of “moral and legal transgression” involves amygdala processing as well.

The thing is, as much as I hate the ugly little thrill of seeing the “bad” guy fall, those initial moral judgements don’t come from nowhere. On the job, “initial schadenfreude occurs when observers appraise mistreatment incidents as relevant and conducive to their goals”. Those initial moral judgements tied to amygdalar and VS activation are a blend of self-interest and genuine “righteous” anger. And so I battle my green demon with a tried and true trick: how would I feel in their shoes?

| Follow more of my work at | |

|---|---|

| Socos Labs | The Human Trust |

| Dionysus Health | Optoceutics |

| RFK Human Rights | GenderCool |

| Crisis Venture Studios | Inclusion Impact Index |

| Neurotech Collider Hub at UC Berkeley |